Google wants to redesign the web in Android's image

This article may contain personal views and opinion from the author.

Microsoft was the next up to show its plans, and that was a far more controversial announcement. Microsoft started by creating the new Metro (now Modern) UI as the design language that would be used across all devices, and introducing the "shared core" between Windows Phone and Windows 8. The Modern UI still has plenty of detractors, especially when it comes to desktop. But, the issue with Windows has always been in the app ecosystem, and Microsoft addressed that with the new universal app development tools shown off a couple months ago. Microsoft still owns the desktop market (although that market is shrinking) and has a solid user base connected to TVs with the XBox, but is struggling to gain share in the mobile world, which would connect its convergence plans of "three screens and a cloud". New CEO Satya Nadella is committed to the cloud, which could mean Microsoft making moves that are similar to Google.

Apple has claimed that it has no plans on converging iOS and MacOS, which sounds a lot like a traditional Apple statement of "it's not true, until it is." The two platforms likely will stay separate for a while, but that doesn't mean that Apple isn't working on having the two platforms work together closely. The beginning of that was unveiled at WWDC this year with the addition of "Handoff". Handoff will allow users to seamlessly continue tasks from a phone or tablet on a Mac, as well as be able to make calls or receive and send texts via a Mac. Apple has started to open up iOS this year with new sharing options and alternative keyboards; so, it's not hard to believe that Handoff could also be opened up to third-party developers as well. But, Apple's world has been a closed system aiming to push users towards content that Apple either controls or curates.

The Android/Chrome OS misdirection

Google's road has been a bit trickier to follow, and a lot of that has to do with the transition from Andy Rubin to Sundar Pichai which happened early last year, but the awkwardness really began back in 2011 when Larry Page took back his spot as CEO of Google, and began work on unifying Google products. According to Businessweek, Andy Rubin was resistant to the plans, and was running the Android division very closed-off from the rest of Google. Rubin's style came to a head in 2012, when Sundar Pichai's team built Chrome for Android. Larry Page wanted Rubin to integrate Google products into Android more and not put as much effort into the stock Android apps. Rubin couldn't do it, so he resigned his position and Pichai took over as the head of both Android and Chrome.

Since then, we have seen the rise of Google Android, including app after app of stock Android being replaced with a Google version, starting with Chrome and moving on to Google Calendar, Keyboard, Camera, and more. It also led to the rise of Google Play services, the framework which gives Google far more control over Android, and creates more hooks to keep users and developers locked-in to the platform. When Andy Rubin was in charge, the assumption had always been that Android would be the platform to make the leap from mobile to desktops, and those plans were in motion. But, when Sundar took over, he killed off those plans in favor of Chromebooks. It's hard to say if that was the right call, because we don't know how well Android laptops would do in the market, but Chromebooks have been far more popular than most ever expected.

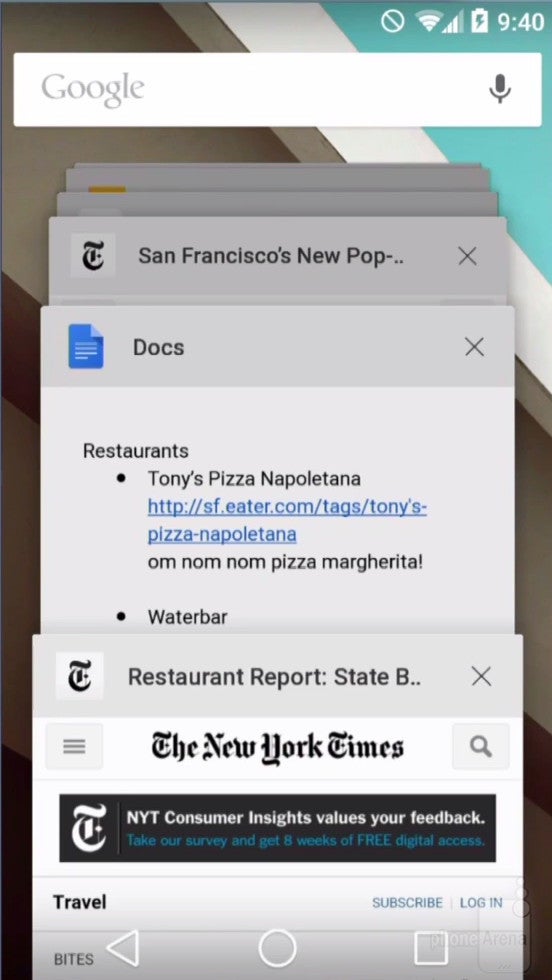

With the success of Chrome OS, the questions began to swirl as to how or if Google would try to merge it with Android. Yesterday, we got the answer to that question in a couple of different ways. First was the obvious: Pichai showed Android apps running in Chrome OS. To be fair, the project was said to be in "early days", so there are a lot of questions left about how it would work; but, it was clear that there are plans to allow Android apps to run on Chromebooks, and have integration for notifications, calls, and text support within Chrome OS. Pichai was very careful to point out one of the major caveats with the feature, which is that Google will "bring your favorite Android applications, in a thoughtful manner, to Chromebooks." Notice that he does not say all Android apps are coming, just "your favorite" apps.

Google doesn't need to converge Android and Chrome, it just needs to make content look native on both delivery methods.

As you may have noticed, talking convergence when it comes to Google doesn't yield a straightforward discussion. Microsoft is unifying Windows and Windows Phone; Canonical is unifying Ubuntu and Ubuntu Touch; and, Apple isn't unifying iOS and MacOS, but is building more connections between the two. With Google, it is easy to claim that the plan is to unify Android with Chrome OS, but that's not quite right, because those aren't really Google's main platform. Google's main platform is the web, which is why Android and Chome can exist separately. Google doesn't need to converge Android and Chrome, it just needs to make content look native on both delivery methods.That's where Google's new design languages come in to play. Most of the focus has been on the new "material design" for Android, but that's only part of the story. Another major piece of the puzzle is Google's new Polymer design project which is "the embodiment of material design for the web", according to Google. Larry Page has succeeded in unifying the design across Google Apps, and now he wants to bring more cohesion to web apps with Polymer. Web apps are obviously a key component to Chrome OS, and Sundar Pichai has shown plans for cross-platform Chrome Apps, but showing how Android L handles web apps proves that content is the real king for Google, because Google isn't striving to unify the design of Android and Chrome. It is trying to unify the design of Android and the Web.

Content is (finally) king

Google has always been a company focused on the web, and the beauty of the web is that it doesn't require convergence. The web is convergence. Google and others have already succeeded in pushing forward HTML5 and kickstarting a rise in more complex web apps. Chrome OS isn't exactly a platform in the traditional sense, it's just a high-powered browser. And, that Chrome browser and Chrome Apps already run on multiple other platforms, meaning there isn't a lot of necessity in converging Chrome OS and Android. The real focus is content. The main trouble with the web is that there is no unifying design language. It is essentially a free-for-all. There are few limitations on web design, and as Matias Duarte just told The Verge, "Design is all about finding solutions within constraint". Material and Polymer create those constraints for the web.

Google Search already has the web covered, that part has been easy. The more difficult part is in mobile apps. For a while now, Google has been working to expand its search capabilities to include in-app content. It has been a slow roll, but Google recently expanded in-app search to include content in English from around the globe, and non-English content is definitely in the works. If Google has its way, content will become the focus. It won't matter if the content comes from a native app or from the web. It may not even matter if you are using Android or iOS, because Chrome Apps will exist on both and Google Search can get at all of it. If Google can get developers to use Material design philosophies and Polymer, web content won't just look like native Android content, but it could begin to hijack iOS as well. In the end, Google is in the business of serving up content (and with that come ads).

Obviously, Google would prefer you to use Android, but whether you do or not won't be as important. Android is a gateway to Google services; Google services allow Google to learn more about you; and, the more Google knows about you, the more money it can make on advertising. The flip side to that is that the more Google knows about you, the better those products can be in offering you the most relevant content and services specifically for you. As much as Microsoft and others may want to paint it as such, Google isn't offering a one-sided deal to take your data and make money. You get value out of the proposition as well.

This is the digital age, data is not a commodity anymore. The value comes from context, relevance, relationships with your audience, and offering a better way to interact with data.

More importantly, content becomes king. Along with the rise of mobile, there has been an annoying trend where content has been put into silos. Apps lock in content, and platforms lock in apps. The aim has been to make information less open and to allow sharing only in certain ways. Web links gave way to apps, and open standards gave way to proprietary solutions often with unnecessary subscription models. From a business perspective, it makes some sense, because sources like The Wall Street Journal and Instagram have to give the impression that their content is somehow special, even though it isn't. This is the digital age, data is not a commodity anymore. The value comes from context, relevance, relationships with your audience, and offering a better way to interact with data. That's Google's plan.With content being the focus and not apps, there isn't much need for converging platforms because the data is already freely available. This was a major theme of Google I/O this year. Android came to wearables, Chrome, TVs, and cars, but Google was clear to say that mobile comes first, meaning it all starts on your phone then moves out from there. The point of it all was to offer ways to get at the same content as always, regardless of where you were and what you're doing. Android is the vehicle, your phone is the hub/controller, and all roads lead to the web, not necessarily to Google Play. This is a stark contrast to Apple's world, where all roads lead to iTunes, and iTunes locks you in to the Apple world.

Google won't say no if you want to lock yourself in to its world via Google Play, but it has to be noted that users can still get value from Google Play Books and Music without ever buying any content from either one. Google Play Music offers storage for 20,000 tracks, and Play Books offers storage for 1,000 books. All of the content put into that storage space could easily be pirated (not endorsed) or purchased from other outlets, and the only real requirement is that books be either ePub or PDF files. It seems reasonable to assume that Google would love to do the same with Play Movies & TV, but would face a hellstorm from the MPAA if it ever attempted that.

This approach is something that Microsoft is also pursuing with its cloud services, the use of various content "hubs" in Windows Phone, and its content stores. But, its success has been more limited, partially due to slow adoption for Windows Phone and Windows 8, and partially because Microsoft is banking more on the app world and making deals with various apps to bring in content. Microsoft's efforts to learn more about users and add contextual organization is only just starting with Cortana, leaving the company well behind Google at least in that respect. Bing isn't quite as far-reaching as Google, but it is getting better as evidenced by universal search in Windows 8 and on the Xbox One, which will surface content from various sources, though not from inside apps. And, new Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella is a cloud guy at heart, so it wouldn't be surprising to see Microsoft and Google going in similar directions going forward. Google has likely been studying the Xbone a bit to learn some lessons for what to do with Android TV, just as Microsoft has been keeping an eye on Google's moves with Drive and Google Now.

Android is the Internet of Things

But, ultimately, it seems unlikely that Microsoft would try to pull an end-around content holders the way Google appears to be. Google is being somewhat careful in its moves. Certain content types, like video, are far more difficult to disrupt than others, although YouTube has been doing a solid job in that respect. Google offers a way around paying for music with the Play Music storage option, but would really rather have users paying for All Access. The real move with Android L, material design, and polymer appears to be Google trying to regain primacy for data that had been part of its link ecosystem in the earlier days of the web, but had been locked into silos in the age of apps.

Google's approach is all about access and context. The apps and the web content are there, and Google Search can find it. Google Now (which is effectively part of Search) learns your habits and feeds out what you probably want to see at a certain time and place. Android Auto, Chromecast, and Android Wear are merely extensions of your smartphone into different contexts. And, the control duties are left up to the best computer you have with you at all times: your smartphone. The main Android platform inhabits phones, tablets, and soon TVs. Google inhabits the web. Android and Chrome deliver that content to you in a way that is easy to consume, but Google still tries to provide the same content through other platforms.

Android is Google's vision for The Internet of Things, where everything in your life is connected to the Internet. Android is malleable and adaptable, but its real strength is its extensibility, something that Apple is just now beginning to allow with iOS. Although it hasn't been fully revealed, extensibility looks like the plan for Nest as well. It just won't be a direct extension of Android. Android Auto and Wear extend the use case of your primary device, likely your phone. The power of this is that is lessens the need to continually update all of the hardware in your life. To a large extent, Android Auto and Wear will gain features as your phone does. You won't really need to worry about updating your car (a relatively difficult thing to do). And, watches are not something that people would normally upgrade on a regular basis, so asking them to start is a tricky proposition, even if the watches in question can start to come in under $200.

Conclusion

Google is obviously doubling down on content, no matter whether it comes from, apps or the web, and attempting to treat everything equally. Or, at least treat it all equally until it gets filtered through Google Now and organized for context and relevance. Google's mission has always been stated as "organizing the world's information", and this appears to be the natural evolution of that. Organization first requires gathering from all sources, and then in presentation, organization becomes tied to personalization. The information that I consume, and how I consume it is likely very different from you. That is the path from Google Search to Google Now. The last piece is in the UI of the presentation, and that's where Google may be over-reaching.

Google is trying to be very smart here, and may be a bit too smart for its own good. The push for material design and polymer has more far-reaching aims that seem apparent at first. Google presented it as a simple unified UI for content on phones, tablets, and laptops. The twist comes when you remember that Google's laptops are just web browsers, which means Google is attempting to create a unified UI for the web. It is an interesting aim, but one that could very well be destined to fail.

Follow us on Google News

Things that are NOT allowed:

To help keep our community safe and free from spam, we apply temporary limits to newly created accounts: