How NSA and GCHQ hacked world largest SIM card maker Gemalto: “game over for cellular encryption”

The initial reaction from security experts: “game over for cellular encryption”

First, we ought to mention that Gemalto has been caught in the blue, and executive vice president Paul Beverly has said the following: “I’m disturbed, quite concerned that this has happened. The most important thing for me is to understand exactly how this was done, so we can take every measure to ensure that it doesn’t happen again, and also to make sure that there’s no impact on the telecom operators that we have served in a very trusted manner for many years. What I want to understand is what sort of ramifications it has, or could have, on any of our customers.”

“It is important to understand that our network architecture is designed like a cross between an onion and an orange; it has multiple layers and segments which help to cluster and isolate data,” Gemalto CEO Oliver Piou said in an amusing analogy used to defeat privacy concerns.

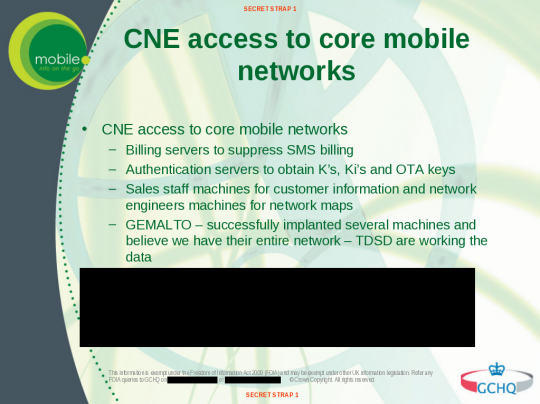

Despite Gemalto's claims, GCHQ leaked slides show that spies believed they had access to their entire network

Still, a lot of serious doubts remain, especially given the fact that Gemalto seemed totally unaware of the attack prior to the Snowden revelations. Earlier, security experts described the events as catastrophic.

“Once you have the keys, decrypting traffic is trivial,” according to Christopher Soghoian, principal technologist at the American Civil Liberties Union. “The news of this key theft will send a shock wave through the security community.”

“Gaining access to a database of keys is pretty much game over for cellular encryption,” according to cryptography specialist at the Johns Hopkins Information Security Institute Matthew Green. Green adds that this is “bad news for phone security. Really bad news.”

How did the spies hack Gemalto?

The way spy agencies attacked Gemalto is also indicative of the methods and intents at play over at the NSA and GCHQ. A secret GCHQ slide reveals that the attack first targeted Gemalto’s internal networks by installing malware on a few computers. Contrary to all of Gemalto’s recent claims, the British spies then conclude that they have gained access to the entire internal network of the SIM card maker.

"WE BELIEVE WE HAVE THEIR ENTIRE NETWORK"

In a coordinated effort, the spies also attacked cell companies’ networks, gaining access to “sales staff machines for customer information and network engineers machines for network maps.” The British spy agency also declares it has control over billing servers, allowing it to hide its hacking activities on an individual’s phone.

The program targeting Gemalto was called DAPINO GAMMA, but the leaked document shows that the GCHQ had been preparing a similar attack against Gemalto rival Giesecke and Devrient.

Understanding encryption: 2G vs 3G vs 4G networks

In order to understand the issue fully, we ought to make a quick recap of digital cellular protocols, starting with the oldest one - GSM.

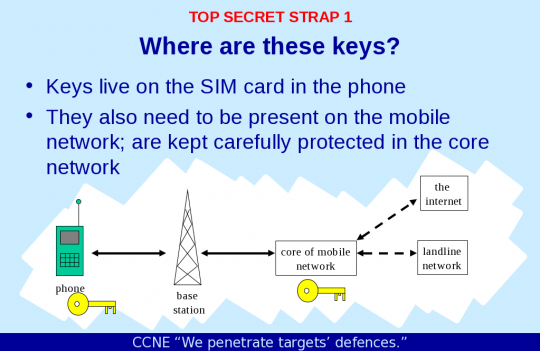

Introduced way back in the 80s, 2G GSM encrypts all calls between the phone and the cell tower via a long-term secret key (referred to as K) stored on the SIM card and at your carrier, BUT the authentication is just one way. The phone authenticates for the tower, but the tower does not need to authenticate back, meaning that anyone with fairly limited budget can create a fake cell tower that a GSM phone will connect to. The fatal flaw of this dated protocol is that the tower picks the encryption algorithm, which basically means that anyone with malicious intents can switch off encryption entirely and spy on communications.

Then, 2G suffers from weak authentication algorithms. 2G encryption uses the A5/1 algorithm that is evaluated to be weak and these days it can be decrypted on a regular PC. Then, there is the even weaker A5/2 algorithm that can be cracked in real-time.

Current day phones in major metros use the much better protected 3G UMTS or 4G LTE standards. These protocols use mutual authentication between phone and tower, done via a MAC that phones verify to legitimize a tower before connecting. Still proprietary, but much stronger authentication algorithms - called f1-f5 - are in use, and call encryption in 3G uses the fairly secure KASUMI block cipher.

The big problem with 3G UMTS or 4G LTE is that attackers with resources can bypass them. The overwhelming majority of phones is made to transition to 2G GSM without much of a notice. This is used by attackers who jam the 3G and 4G connections, forcing your phone to connect back to 2G GSM, and use all the aforementioned attacks.

A good example of the huge implications for this is the country of Ukraine, which is probably the only European country that lacks 3G infrastructure. There have been multiple cases of individuals eavesdropping on politicians using nothing but a compact antenna and a laptop, a setup that costs a few thousand dollars.

The Gemalto revelations are important because they can be used without having to go into the complexities of breaking the cryptography flaws we described above. Having access to the weak chain in the link that is the encryption keys means that phone calls can be decrypted and spied on months and even years after they have been made.

The implications of this are huge, and undermine SIM card security and communication via the standard dialer and messaging apps. With Gemalto being a supplier of cards to nations across the globe, ranging from the European Union to China and Russia, the effects of this latest leak will have an immediate effect on a global scale. On a personal user level, the solution to the problem is to use secure messaging and calling apps like Silent Phone for encrypted voice calls and Signal for encrypted texts. Email communication from the big providers uses the Transport Layer Security (TLS), and is also considered safe.

source: The Intercept, WSJ, CryptographyEngineering

Introduced way back in the 80s, 2G GSM encrypts all calls between the phone and the cell tower via a long-term secret key (referred to as K) stored on the SIM card and at your carrier, BUT the authentication is just one way. The phone authenticates for the tower, but the tower does not need to authenticate back, meaning that anyone with fairly limited budget can create a fake cell tower that a GSM phone will connect to. The fatal flaw of this dated protocol is that the tower picks the encryption algorithm, which basically means that anyone with malicious intents can switch off encryption entirely and spy on communications.

Current day phones in major metros use the much better protected 3G UMTS or 4G LTE standards. These protocols use mutual authentication between phone and tower, done via a MAC that phones verify to legitimize a tower before connecting. Still proprietary, but much stronger authentication algorithms - called f1-f5 - are in use, and call encryption in 3G uses the fairly secure KASUMI block cipher.

The big problem with 3G UMTS or 4G LTE is that attackers with resources can bypass them. The overwhelming majority of phones is made to transition to 2G GSM without much of a notice. This is used by attackers who jam the 3G and 4G connections, forcing your phone to connect back to 2G GSM, and use all the aforementioned attacks.

ALL OF THIS DOES NOT MATTER, IF YOU HAVE THE ENCRYPTION KEY

The Gemalto revelations are important because they can be used without having to go into the complexities of breaking the cryptography flaws we described above. Having access to the weak chain in the link that is the encryption keys means that phone calls can be decrypted and spied on months and even years after they have been made.

Conclusion

The implications of this are huge, and undermine SIM card security and communication via the standard dialer and messaging apps. With Gemalto being a supplier of cards to nations across the globe, ranging from the European Union to China and Russia, the effects of this latest leak will have an immediate effect on a global scale. On a personal user level, the solution to the problem is to use secure messaging and calling apps like Silent Phone for encrypted voice calls and Signal for encrypted texts. Email communication from the big providers uses the Transport Layer Security (TLS), and is also considered safe.

source: The Intercept, WSJ, CryptographyEngineering

Follow us on Google News

Things that are NOT allowed:

To help keep our community safe and free from spam, we apply temporary limits to newly created accounts: